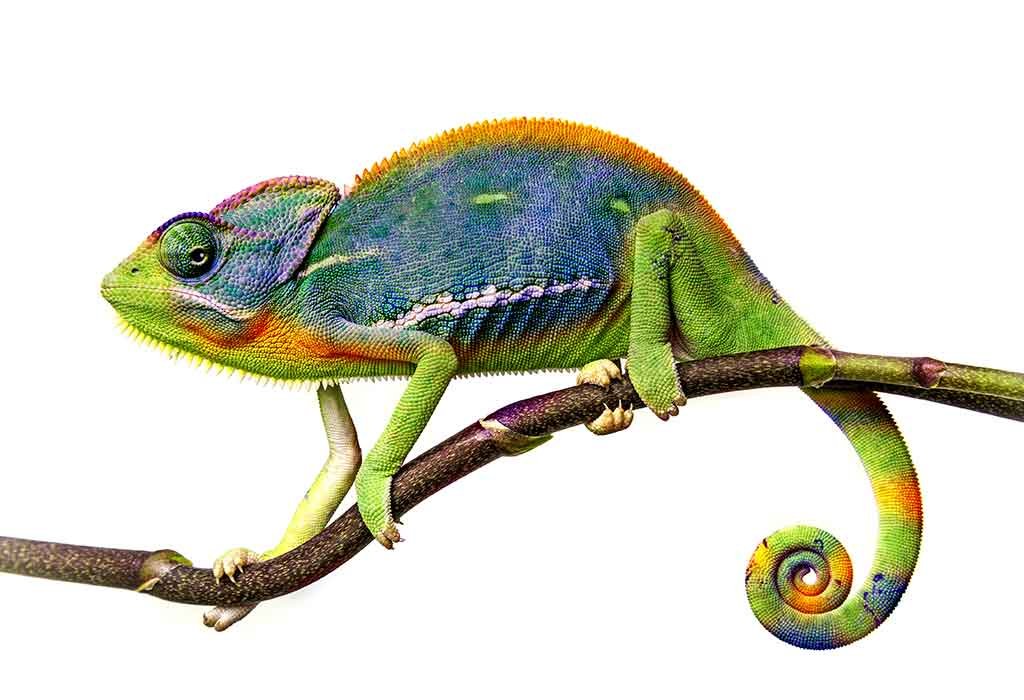

Chameleons are remarkable creatures known for their color changing abilities, large eyes that swivel independently, extendable tongues, and prehensile tails.

These iconic lizards have captivated humans for centuries due to their uniqueness. But perhaps the most fascinating aspect of chameleons is their extraordinary capacity to regenerate lost tails.

When threatened by predators, chameleons can voluntarily shed their tails through a process called autotomy. Afterwards, the tail undergoes an intricate and multi-stage regenerative process to regrow the lost appendage.

Understanding chameleon tail regeneration provides intriguing insights into the incredible self-healing abilities of nature. It also has important implications for regenerative medicine and may provide a blueprint that can be translated to develop novel therapies for humans suffering from loss of tissue or organs.

By exploring the various facets of this phenomenon, scientists are unraveling nature’s secrets about repairing damage and reversing the effects of trauma.

An Introduction to Chameleons

Chameleons belong to the family Chamaeleonidae, which contains over 210 species. They are part of the larger Iguania suborder of lizards, which also includes iguanas and agamids.

Chameleons are native to parts of Africa, Europe, Asia, and the islands of Madagascar, Seychelles, and Comoros. The name “chameleon” is derived from the ancient Greek words chamaeleon meaning “ground lion”.

These arboreal reptiles have a number of adaptations that allow them to blend into their surroundings, including the renowned color changing ability. Other distinctive features are:

- Independent eye movement – Chameleons can swivel and focus each eye separately to survey a wide field of vision for predators and prey.

- Zygodactylous feet – The feet are fused into bundles of 2-3 opposable digits to grip branches.

- Projectile tongues – Tongues can extend rapidly up to twice the body length to catch prey.

- Prehensile tails – The tail can wrap around branches and act like a fifth limb for balance and climbing.

Chameleons are slow moving, solitary animals that feed primarily on insects like flies, crickets, locusts, and mantises.

Their unique features allow them to efficiently detect prey and climb through trees and vegetation where many species spend their entire lives.

While famous for color change, the primary functions are actually thermoregulation, communication, and camouflage.

Tail Autotomy – Shedding to Survive

Many lizards have developed the ability to lose their tails under threat, known as caudal autotomy. When preyed upon, they can sever their tails allowing them to flee with reduced weight and distraction of the still wiggling tail.

The detached tail continues to wiggle after being dropped to attract the predator’s attention. This improves the lizard’s chances of escaping by diverting the predator.

While losing a limb or appendage may seem drastic, it is an effective survival adaptation. This is especially true for arboreal lizards like chameleons, where a quick getaway to avoid falling is critical. Some key facts about tail loss in chameleons:

- Triggered by strong bites or other trauma – signals sent to initiate autotomy

- Can voluntarily shed the tail when threatened

- Uses an “autotomy plane” – a weak joint where the tail breaks off easily

- Minimal blood loss occurs during shedding

- Tail keeps moving after detachment, sometimes for over an hour

“The chameleon’s tail is not just a tool, it’s a teacher. It whispers tales of adaptation, of bending before the storm, and rising anew, stronger than before.” – Kaia Sunfeather, Nature Poet

Shedding a tail does incur costs such as temporary loss of fat reserves and sensory inputs. It also impairs balance which is important for arboreal maneuvers.

However, the benefits outweigh these costs in life or death situations. Without a quick escape, chances of ending up as prey are much higher. Tail loss allows the animal to fight another day.

Regrowing the Lost Tail – A Complex Feat

While losing a tail provides an immediate advantage against predators, chameleons need their tails to thrive long-term.

The tail comprises about half the length of a chameleon and serves multiple important functions:

- Balance – Important for moving on branches and reaching for food in trees

- Grasping – Prehensile tails can grip branches like an extra limb

- Energy storage – Tails contain fat reserves

- Signaling – Used for communication displays and attracting mates

To regain these vital functions, chameleons have evolved the capacity to regenerate new tails through an intricate process of regrowth.

Within days after autotomy, specialized cells known as a blastema form at the site of the wound. These cells are the key players that drive the regeneration process.

The blastema possesses stem cell-like properties, allowing the cells to differentiate into various tissue types needed to rebuild the tail. The new tissues generated include:

- Bone – Formed through osteogenesis by osteoblasts in the blastema

- Cartilage – Formed through chondrogenesis by chondrocytes

- Blood vessels – To supply nutrients and oxygen to regrowing tissues

- Nerves – To restore sensation and function

- Skin – To recreate the outer barrier and scales

- Muscle – To power tail movement

Remarkably, most of these tissues emerge in the original order they appeared during embryonic development of the tail. The regenerated tail can reach full length within 2-3 months in many chameleon species.

“Each lost tail is a blank canvas, a chance for the chameleon to rewrite its story. The new tail may not be the same, but it bears the marks of resilience and the whispers of survival.” – Dr. Maya Patel, Herpetologist

However, there are limits to this regenerative capacity. The new tail is simpler in structure, without the vertebrae and complete vasculature of the original.

After the first detachment, subsequent regenerations result in smaller and more rudimentary tails. The illusive ability of perfect regeneration remains out of reach.

The Incredible Biology Underlying Tail Regrowth

The ability to regenerate lost body parts is exceedingly rare among vertebrates, making the chameleon’s regenerative power all the more remarkable.

Scientists have extensively studied their tails to uncover the biological secrets behind regeneration.

These studies have revealed a number of key cellular events and signaling pathways that enable the process:

- The Wnt signaling pathway controls cell differentiation and growth during tail regeneration.

- The Sonic hedgehog pathway patterns the new tail and guides development.

- Fgf signaling regulates formation of the blastema.

- The Bmp signaling pathway directs bone regeneration.

- Epigenetic changes in gene expression drive cellular plasticity.

- MicroRNAs fine tune gene activation involved in regrowth.

In essence, chameleon cells reboot their programming, dial back the clock, and recreate the orchestrated genesis of embryonic tail formation.

But how do the cells know what to do and when to do it after injury? This remains a central mystery regeneration biologists continue investigating.

Unlocking the complex cellular choreography of regrowth has profound implications for medicine and therapeutic approaches.

“Within the humble stump of a severed tail lies a universe of potential. The chameleon holds the secret to unlocking the body’s hidden blueprint, a map to regrow what was lost.” – Professor Elias Sanchez, Regenerative Biology

The Costs and Benefits of Tail Autotomy

The regenerative powers of the chameleon’s tail come at a price. Regenerating the tail is an extremely energy intensive process for the animal.

Studies show tail loss and regrowth can reduce fat stores by over 40% and decrease sperm production in males. This leads chameleons to invest heavily in extra feeding and rest after shedding their tails.

They also become more vulnerable to predators during the regeneration period.

But the payoff from regenerating the tail makes the efforts worthwhile. The regrown tail eventually provides vital functions that aid the chameleon’s survival and reproduction. Advantages include:

- Restoration of balance and climbing ability in the trees

- Reestablishment of fat reserves in the tail

- Renewed sensory inputs from the tail

- Reinstatement of display and grasping abilities

These provide key selective advantages that likely drove the evolution of tail regeneration abilities in chameleons and other lizards.

Surviving a predator attack is the first step, but regenerating the tools needed to effectively hunt, feed, mate, and thrive is the final achievement.

However, there are diminishing returns after multiple autotomies. Research shows chameleons faced with repeated tail losses from frequent attacks will regenerate smaller and more rudimentary tails.

There is a limit to how often chameleons can tap into their regenerative powers before permanent impairment sets in.

Factors That Impact Tail Regrowth

The regeneration competency of chameleons depends on numerous factors. While their cells may possess latent regenerative potential, actually realizing this potential requires optimal conditions.

Some variables that affect tail regrowth include:

Age

- Younger chameleons regenerate tails faster and more completely than older animals. Their cells are more plastic and potent.

Overall Health & Nutrition

- Good general health and adequate nutrition provide the energy and raw materials needed for regrowth. Deficiencies in protein, vitamins, or minerals can impair the process.

Infection

- Open wounds are prone to microbial infection which can hinder or even halt regeneration if severe enough.

Stress

- High stress due to factors like poor habitat quality elevates cortisol which can suppress the immune system and regeneration.

Habitat

- Chameleons from intact forests with ample food and fewer predators tend to regenerate better than animals from highly disturbed or fragmented areas.

Genetic & Epigenetic Factors

- The genes encoded in the chameleon genome and chemical tags on DNA that control gene expression impact regenerative potential.

Gaining a handle on these variables could potentially allow for interventions to accelerate and enhance regeneration. This could help offset impairments and improve outcomes and survival for chameleons with autotomized tails.

“Watching a chameleon regenerate its tail is like watching hope take shape. It’s a reminder that even in the face of loss, there is always the potential for renewal.” – Avani Silva, Conservationist

The Evolutionary Advantage of Tail Regeneration

Most evolutionary biologists agree that the selective pressure of escaping predators is likely what drove the development of tail autotomy and regrowth in lizards.

Fossil records indicate caudal autotomy evolved around 200 million years ago in archosaurs, the ancestors of modern crocodiles and dinosaurs. Chameleons likely co-opted the same biochemical pathways for regeneration later on, around 80 million years ago.

The threat of being eaten supplied a strong incentive to evolve this mechanism. Several lines of evidence support the predator escape advantage:

- Well-documented predator distraction tactic used by detaching tail

- High rates of non-fatal tail loss observed in wild chameleon populations

- Regenerated tails retain coloration and movement ability

- Persistence of regrowth capacity despite high energy cost

Beyond predator evasion, a new tail allows chameleons to recoup other survival benefits like balance, climbing, fat storage, and mating displays. Together these factors provide a significant selective advantage.

Chameleons born without the innate capacity to regenerate tails likely did not survive and reproduce at the same rates over evolutionary timespans.

However, it is still unknown exactly when and how chameleons originally evolved this ability.

Further research into the paleobiology and evolutionary genomics of chameleons is needed to fill in the gaps about the emergence of tail regeneration in these intriguing lizards.

Tail Loss Threats and Impacts on Chameleon Conservation

While an autotomized tail can spell salvation for a chameleon in the moment, predator attacks and tail loss also pose troubling implications for conservation.

Ongoing habitat loss and fragmentation are increasing interaction rates between chameleons and predators. Human encroachment is also increasing collection pressures for the pet trade and traditional medicine uses.

More frequent predator encounters and captures lead to elevated tail loss. Multiple successive losses can diminish the storage and signaling functions of tails.

Impaired balance and climbing further reduce ability to effectively navigate arboreal habitats. Diminished fat reserves may also negatively impact reproduction and fertility.

Together these pressures threaten the viability of local populations already facing dwindling habitat and isolation.

Researchers studying chameleon communities in disturbed or fragmented forests note higher rates of injury and tail loss. Preventing the downward spiral caused by tail impairment will be key for reversal.

Some actions that can aid regeneration and conservation efforts:

- Protecting intact forest corridors to allow migration

- Reducing pressures from illegal collection

- Creation of nature reserves with restricted human access

- Habitat restoration around fragmented forests

- Public education about chameleons to increase support for conservation

“The chameleon’s tail is a living testament to the interconnectedness of all things. Its loss and regrowth ripple through the ecosystem, whispering secrets of balance and interdependence.” – Chief Waku, Cherokee Elder

Without intervention, the remarkable capacity of tail regeneration could itself be diminished and lost in nature. Researchers have a responsibility to ensure their work also translates to improved well-being for these marvelous animals.

Potential Medical Applications Inspired by Chameleon Tails

The regrowth abilities of chameleons have captured the imagination of regenerative medicine researchers seeking to find ways to heal wounds and replace lost tissues in humans.

Studying the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in chameleon tail regeneration has yielded tantalizing clues that could be applied to develop new medical therapies. Some promising areas of research inspired by chameleon tails include:

Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Medicine

- Using biocompatible scaffolds seeded with stem cells to reconstruct damaged bones, nerves, and other tissues

Gene Therapy & Gene Editing

- Manipulating genes and signaling pathways involved in regeneration to enhance wound healing

Epigenetic Drugs

- Pharmaceuticals targeting epigenetic modifiers of gene activity to promote regeneration

Bioelectric Medicine

- Using devices that modulate electric currents in cells and tissues to stimulate regeneration

MicroRNA Therapies

- Introducing microRNA molecules to alter cellular differentiation and growth programs

Biochemical Factors

- Identifying proteins and small molecule compounds produced during chameleon tail regrowth that could be administered as drugs

Organoid & Bioreactor Models

- Growing 3D tissue models with chameleon cells to screen drug candidates and understand regeneration

“Humans envy the chameleon’s tail, this magical appendage that defies the finality of loss. But perhaps, the true magic lies not in regrowth, but in the acceptance of change, the dance between letting go and starting anew.” – Li Wei, Zen Master

However, major hurdles remain before regenerative therapies become widely viable solutions. Extensive clinical trials and experimental validations with human cells and tissues are needed to translate findings in chameleons safely to medical practice.

Key Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Directions

While recent decades have brought major advances, many central mysteries still surround the phenomenon of chameleon tail regeneration.

Filling key knowledge gaps will be critical for gaining full insight and maximizing the potential applications inspired by their tails. Some questions that remain to be answered by ongoing research include:

- How is the precise patterning of the regenerated tail achieved? What provides the developmental instructions?

- What is the full suite of genes, proteins, and signaling pathways involved? Many remain unknown.

- How are stemness and pluripotency sustained in blastema cells undergoing repeated injury and regeneration?

- What is the role of the immune system? More focus is needed on these mechanisms.

- Can methods be developed to experimentally enhance regeneration in chameleons?

- How does regeneration change with aging at the cellular level? Can age-related declines be reduced?

- What microbial communities inhabit the skin and tissue of tails? How do they influence regeneration?

- Can genome editing and transcriptomics unravel gene regulatory networks controlling regrowth?

- How can organoid culture systems best mimic the 3D cellular dynamics of regenerating tails?

Addressing these open questions, and undoubtedly many more that arise, will require extensive integrated research efforts combining genetics, developmental biology, bioinformatics, tissue engineering, and other approaches.

But the payoff from diving deeper into the biology of chameleon tail regeneration will be rewards that resonate far beyond the walls of the laboratory.

“Let the chameleon’s tail be a beacon of inspiration. May we face our own losses with courage, and embrace the possibility of growth, even from the ashes of what was.” – Anonymous

The Critical Importance of Scientific Rigor and Ethics

As researchers continue probing the remarkable regenerative abilities of chameleons, it is paramount that work is conducted ethically and meets the highest standards of scientific rigor.

Animals should never be harmed or stressed in the name of science. Some considerations for ethics include:

- Using the minimum number of chameleons needed to gain meaningful data

- Prioritizing lab techniques like organoids that avoid use of live animals

- Providing enriching captive environments when animals are studied

- Avoiding repetitive tail amputation – autotomized tails regenerate naturally

- Returning rehabilitated chameleons to the wild whenever possible

Additionally, transparency, reproducibility, and critical peer review must be at the core of all studies. Overhyping claims without thorough validation compromises progress.

Integrity to the scientific process ensures findings stand the test of time and benefit both chameleons and humankind.

Conclusion

The remarkable capacity of chameleons to regenerate their tails provides a window into nature’s ingenious solutions for restoring lost tissues and appendages.

Chameleon tails regrow through a complex series of cellular and molecular events, guided by signaling circuits that spur focused growth and re-assembly of intricate structures.

Studying this extraordinary process continues to reveal principles about biology’s latent

potential for healing and renewal. While chameleons can currently achieve only partial regeneration, their tails provide a starting point to uncover the blueprint for one day realizing the full regenerative abilities encoded within our own genome.

Much remains to be learned about the intricacies of chameleon tail regrowth and how to translate these findings to improve medical care. As researchers persist in their quest to demystify nature’s regenerative power, they must also honor their ethical duty to avoid undue harm.

Within the graceful dance of shedding and regenerating the tail lies profound teachings about change, adaptation, and the persisting force of life.

May the mysteries of the chameleon tail continue to inspire imagination, hope, and discovery for many generations to come.

Leave a Reply